Who’s done the Chaco Canyon supernova hike? The trail that takes you to a pictograph of a hand, crescent moon, and a ten pointed star that some archaeologists believe represents the 1054 CE supernova, an explosion so bright it lit up the daytime sky for weeks?

It’s a cool glyph, but in honor of the upcoming solar eclipse, we wanted mention a lessor known Chaco Canyon petroglyph that Jośe Vaquero from the Applied Physics Department of the Universidad de Extremadura, Cáceres, Spain and J. McKim Malville of the Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences Department of the University of Colorado think is a depiction of the 1097 CE solar eclipse.

Of course there isn’t a way to really know what Chacoan glyphs mean. Even now not everyone agrees with the hand/moon/star pictograph supernova idea. Nonetheless, compelling arguments can be made, which is exactly what Vaquero and Malville set out to do.

To validate their claim, they start with the “eclipse” petroglyph’s location. It was etched into Piedra del Sol, a boulder in Chaco Canyon that researchers say marks the summer and winter solstices. The scientific duo also point to 2008 research that proves the 1097 CE total solar eclipse was visible from Chaco Canyon. To round out their argument, Vaquero and Malville turn to the petroglyph’s design.

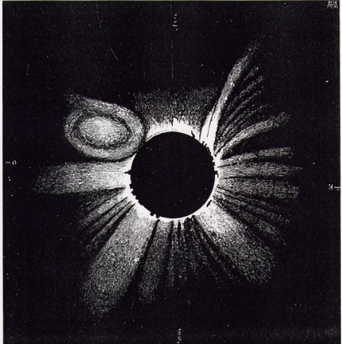

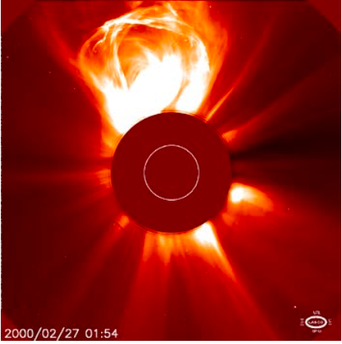

The pair says the petroglyph, which Malville describes as looking “like a circular feature with curved tangles and structures,” looks like 20th century renderings of solar eclipses occurring in conjunction with coronal mass ejections (CME), and it is their contention that the Chaco Canyon petroglyph does in fact depict a CME.

To add scientific evidence to a hypothesis they know cannot be proven to be true, they set up a method by which it could be tested and at least proven false. To do so they relied on astronomy’s knowledge of the sun.

According to Vaquero and Malville, the sun reaches a highly active stage every eleven years or so and starts producing coronal mass ejections up to three times per day. To figure out if the sun was highly active during the 1097 CE eclipse, the scientists scoured historical records looking for accounts of auroras and sunspots, both indicative of high sun activity.

Vaquero and Malville also looked at “cosmogenic radionuclides,” produced by cosmic rays hitting the earth’s atmosphere during high points of solar activity. The cosmic ray concoction creates measurable concentrations of radiocarbon that can be seen in tree rings. In 2004 a scientific group assembled tree ring carbon data to produce dates for high solar activity, so Vaquero and Malville added the tree ring data to their pile.

By the end of their study, the pair concluded that the 1097 CE solar eclipse did come at a point of high solar activity, meaning they have proven their petroglyph hypothesis is not not true.